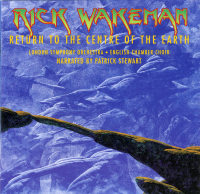

Return to the Centre of the Earth

| Return to the Centre of the Earth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 15 March 1999 | |||

| Recorded | March–December 1998 | |||

| Studio | POP Sound (Santa Monica, California) CTS Studios (Wembley, London) The Jacaranda Room (Hollywood, California) A&M Studios (Hollywood, California) Bajonor Studios (Isle of Man) The Dog House Studio (Henley-on-Thames, England) | |||

| Genre | Progressive rock | |||

| Length | 76:51 | |||

| Label | EMI Classics | |||

| Producer | Rick Wakeman | |||

| Rick Wakeman chronology | ||||

| ||||

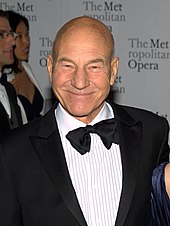

Return to the Centre of the Earth is a studio album by English keyboardist Rick Wakeman. It was released on 15 March 1999 on EMI Classics and is the sequel to his 1974 concept album Journey to the Centre of the Earth, itself based on the same-titled science fiction novel by Jules Verne. It tells a new story of three unnamed travellers who attempt to follow the original journey 200 years later, but from a different entrance. It is narrated by actor Patrick Stewart.

Ideas for a sequel developed in 1991 with initial plans for a 1994 release, the twentieth anniversary of the original. After Wakeman produced a demo tape of songs, he caught the interest of EMI Classics who signed him to a recording deal and supplied an advance to record it. The album features the London Symphony Orchestra, the English Chamber Choir, and guest performances by Ozzy Osbourne, Bonnie Tyler, Tony Mitchell, Trevor Rabin, Justin Hayward, and Katrina Leskanich. In 1998, production halted after Wakeman was hospitalised with a life threatening case of pneumonia and pleurisy.

The album was Wakeman's most significant album of the decade and peaked at No. 34 on the UK Albums Chart, his first UK Top 40 hit in 18 years, but failed to make a commercial impact in the US. Wakeman performed the album in its entirety with his rock band, orchestra, and choir, in 2001 and 2006, both times in Canada. A deluxe box set with live and previously unreleased audio and video material was released in 2021.

Background

[edit]In 1974, Wakeman released his second solo album Journey to the Centre of the Earth, a concept album based on the same-titled science fiction novel by Jules Verne. It tells the story of Professor Lidenbrook, his nephew Axel, and their guide Hans who follow a passage to the Earth's centre originally discovered by Arne Saknussemm, an Icelandic alchemist. The idea to produce a sequel album first came to Wakeman in 1991 during a solo tour of Italy, when a journalist suggested to record a new and extended version of Journey with new technology. Several weeks later, during the Union Tour with Yes, Wakeman set up the tentative plan of re-recording the album live in concert with added music for a prospective release in 1994, the twentieth anniversary of the original.[1] During the tour's stop in New York City, Wakeman visited the office of Arista Records and pitched the idea to an acquaintance, but was turned down. Wakeman recalled, "He said ... you recorded and wrote [Journey] with what you knew existed with instruments and recording techniques, so you pushed as far you could go. Now if you do it again, is different because you would not be pushing anything".[1] Wakeman was advised to put the idea on hold and think about a new "epic" album with a new story and music, of which he'll "know when the right time is".[1]

Wakeman pursued other projects until idea was revived in 1996 when, in a two-month period, four record companies expressed an interest to fund and release a new "epic" album from him. "By the time of the first call I thought, 'Perhaps this is what my friend [at Arista] meant, because it appears to be a good time'".[1] One label soon dropped out, but the remaining three were still interested and Wakeman began to develop the concept. He read Verne's other famous novel, Around the World in Eighty Days, and started to write music, but scrapped the idea partly due to Richard Branson's world record attempts to circumnavigate the Earth by hot air balloon and the possibility of people relating the music to the event.[1] Wakeman subsequently read a newspaper article by Steven Spielberg, "who was talking about have sequels for making films, how you have a story and you spin up from the story for a whole new story, but you have a relationship, which is very comfortable for the people who listen a whole new story, new characters, but there's still a relationship."[1] This prompted him, after revisiting the original Journey novel, to have the album tell a new story, set 200 years later, of three travellers who attempt to follow the original route but descend from a different entrance.[2] Wakeman wrote the story as if he was Verne writing a sequel, and purposefully unassigned names or genders for the travellers, "because they could be the person listening".[1][3]

Wakeman's idea was well received by the three record companies, and he was asked to produce a demo tape of some songs, narration, and orchestral parts. He approached this by looking back at working with David Bowie on his album Hunky Dory (1971), which he used "as a parallel to get the best out of myself."[3] He usually produced demos with the keyboard parts "in pretty solid form" with musicians playing around them, but this time he produced a demo of the entire track on the piano and asked guitarist Fraser Thorneycroft-Smith, bassist Phil Williams, and drummer Simon Hanson to play parts as if they were his own songs. "By the time I came to put my own parts on I had to play the keyboards totally differently to the way I would do normally."[3] A problem arose when Wakeman was asked about his backing band as he wished for them and the orchestra not to be restricted to one style, and in his mind saw each group perform a variety of styles, playing "rock things, heavy metal ... I want the band playing a classical thing".[1] Despite being told to continue with the demos regardless, Wakeman was concerned whether his idea was understood properly by the record labels; his two eldest sons, Oliver and Adam Wakeman, advised him not to do the album if it could not be produced to his liking.[1] Wakeman came close to shelving the entire project until Nic Caciappo, an editor of the Yes information service and magazine in California, told his friend Dwight Dereiter of EMI-Capitol at a dinner about Wakeman's problem. A synopsis of the album was sent to Dereiter, who liked it and forwarded it to the European office of EMI Classics, the label's classical music division, as he thought they would understand it better.[1] With assistance from Frank Rodgers of music publisher The Product Exchange, who soon took over as management for the project, the idea arrived at label president Richard Lyttelton, who discussed the album with Wakeman over lunch in February 1998. Lyttleton offered a recording contract and to supply £100,000 to help with costs, which Wakeman accepted.[1][4]

Recording

[edit]Recording began in March 1998 and took place in six different locations, including Wakeman's home studio named Bajonor on the Isle of Man.[2] The album had a running time of 126 minutes in its original form, which Wakeman reduced to around 80 minutes so it could fit a single CD. The result, Wakeman said, resulted in a more "direct" album.[5] It was recorded using Sony 48-track machines with Wakeman playing 13 different keyboard instruments.[3] Wakeman declined to play any of the music to his family, which Oliver considered strange as he usually shared his musical work with them. Adam assisted in the choir arrangements.[5]

Lyttelton wanted Wakeman to record the album with musicians that he had never worked with before in order to push Wakeman and the album to "new limits". The idea was strange to Wakeman at first as he already had his rock band The English Rock Ensemble available to perform, but later said Lyttelton was "100% right".[5] Wakeman was free to pick lead vocalists of his choosing, with Lyttleton suggesting that he use "the right singer for the right song".[5] He had written four songs with a specific vocalist in mind, but two other pieces, "Ride of Your Life" and "Mr. Slow", with no one in mind. Wakeman felt the former needed a "raunchy female rock vocal", to which a chance comment to a colleague led to contact with Katrina Leskanich, who agreed to participate.[3] Tony Mitchell sang on "Mr. Slow" after Wakeman's engineer Stuart Sawney was assisting with the recording of the drums at Barriemore Barlow's studio. Barlow suggested Mitchell after hearing an album from her band Kiss of the Gypsy.[3] "Buried Alive" is sung by Ozzy Osbourne, "Is Anybody There?" by Bonnie Tyler, "Never is a Long, Long Time" by Trevor Rabin, and "Still Waters Run Deep" by Justin Hayward.[2]

A narrator was not decided upon until shortly before Wakeman signed with EMI. Gilbert Heatherwick, the head of EMI's US division, asked who would take the role and suggested English actor Patrick Stewart. Wakeman was aware that booking Stewart would result in higher costs, but Lyttelton liked the idea and made it happen. Stewart's parts were recorded at POP Sound Studios in Santa Monica, California in August 1998. The session was originally booked for two hours, but Stewart enjoyed the experience so much he allowed the session to continue for the entire day at no extra cost, and cancelled his other scheduled arrangements.[5] Stewart's narration was placed on the odd-numbered tracks on the CD, with the music placed on the even ones. Wakeman wanted the songs to run parallel with the story, as opposed to the original Journey album where the songs told the story along with the narration.[3]

Recording was disrupted midway through due to Wakeman's failing health. For three months, he worked 22-hour days which took a toll on him mentally and psychically.[6] In August 1998, shortly after his trip from Los Angeles to record Stewart's narration, Wakeman collapsed on a golf course and was rushed to hospital. He was diagnosed with a life threatening case of double pneumonia and pleurisy, and showed signs of Legionnaire's disease. At one point, his doctors gave him just 48 hours to live.[6] The setback led the recording sessions with the orchestra to be rearranged for December 1998.[5]

Wakeman originally suggested to use a symphony orchestra and choir from Belgrade with an unknown narrator to keep costs at a minimum, but Lyttelton was happy to employ a well known one and later was glad he "resisted the temptation" to go with Wakeman's idea as he wanted to make the album "to the fullest".[5] The two agreed to use the London Symphony Orchestra with conductor David Snell and the English Chamber Choir conducted by Guy Protheroe, which cost £122,000.[5] Recording took place across two days at Studio 1 at CTS Studios in Wembley, London, both days consisting of two three-hour sessions.[3] Wakeman recalled the experience as the most nerve-racking experience of his music career at that time. Shortly before the orchestra played, he recalled: "I will hear for the very first time whether at all the arrangements I have done will work, will sound perfect or whether it'll sound terrible, as if the LSO was a third rate brass band. I asked myself what these EMI directors would've done if it had sounded terrible. ... Those final twenty seconds have been the most silent twenty seconds of my life. As if in slow motion I saw the baton going up and even when I only heard a rough mix in the control room it was as if thick clouds were making way for the sun to emerge. That moment all stress left my body as I turned around and only saw laughing faces. If I still had doubts, they all left that same instance."[5] Two additional days were booked with the orchestra on stand-by in case parts needed to be re-recorded, but they were not used. Recording moved to Studio 2 to work on editing and putting down overdubs.[3]

The cover is Wakeman's first to be designed by Roger Dean, who produced artwork for several Yes albums.[3] When recording for the album was finished in December 1998, almost 300 people were involved with its production.[2] It cost £2 million to produce, a significant amount in comparison to Wakeman's earlier albums which were produced on small budgets.[5][7] Wakeman heard the album in its entirety for the first time on 17 December 1998, and received a CD of it in mid-January 1999.[5]

Release and reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| About.com | (mixed)[8] |

| Birmingham Evening Mail | (mixed)[9] |

| The Boston Herald | |

| Allmusic | |

On 9 February 1999, the album received a 300-guest launch party arranged by EMI at the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, London.[5] The album's release followed on 15 March.[12][13] A promotional radio edit of the album was made with the songs edited to around four minutes, and distributed to radio stations to allow the album to gain airplay.[5] A limited edition vinyl was also released with a single run of 35,000 copies.[3] It reached a peak of number 34 on the UK Albums Chart during its three-week stay on the chart. EMI set a goal of selling 300,000 copies of the album worldwide, but sales had only reached 195,000 copies two years after its release. Targets were met in each territory except the United States, where just 25,000 copies were sold which Wakeman felt disappointed about.[14] Ideas to turn the album into an IMAX film were scrapped.[3]

The album received mixed reviews from music critics. The Birmingham Evening Mail wrote the album is "twice as long and equally as ambitious" as the original and rates Stewart's "precise narration". The orchestra and choir "enter into the spirit of things with gusto", but the review concluded with "expect a punk rock backlash in the year 2001".[9] A review in The Boston Herald by Kevin R. Convey gave the album 1-and-a-half stars out of five, saying Wakeman "hasn't lost his touch" and that the sequel "is every bit as pompous and bombastic as the original", which contained a "thoroughly silly script" for its narration and "risible" lyrics. Convey concluded: "Those who love Journey probably will enjoy this as well. Others may want to find more creative ways to give themselves a headache".[10] In October 1999, a review from Shawn Perry for About.com praised Stewart's performance for his "infectious precision" in his narration and the album's opening of "lush orchestrations, slyly garnishing Stewert's poignant articulations throughout". Perry thought Wakeman's keyboards sound "seemingly shrouded ... certainly not as distinctive as Wakeman's sound can be", but welcomed "Buried Alive" as the point when the album "sonically surges forward" and for Osbourne's vocals and Wakeman's solo. From then on, Perry thought the album takes an "ethereal tone ... with no real central theme to convey" but considered Tyler's and Hayward's songs as highlights. Perry concluded that the album acts as a "self-fulfilling aspiration" for Wakeman, and thought the audience lack the patience to sit through the album.[8]

Live performance

[edit]Initially, Wakeman wanted to perform the album on the Spanish island of Tenerife, as close to Mount Teide as possible, with the Orquesta Sinfónica de Tenerife, but the difficulties in performing around such an ecological area led to the idea being scrapped.[1] Material from Return to the Centre of the Earth was performed live for the first time as part of Wakeman's 25-date Half a Century Tour, playing a selection of material across his career in churches and cathedrals across the United Kingdom from May 1999.[15] A full scale tour with a stage designed by Dean was shelved.[5]

Wakeman has performed the album live in its entirety twice, both times in Québec, Canada. The premiere took place on 30 June 2001 in Trois-Rivières with Wakeman's band the English Rock Ensemble, then formed of his son Adam Wakeman on keyboards, guitarist Ant Glynne, bassist Lee Pomeroy, and drummer Tony Fernandez. Vocals were performed in English by Luck Mervil and Fabiola Toupin. The second performance followed on 15 July 2006 on the Plains of Abraham, Quebec City as part of the annual Quebec City Summer Festival. Wakeman was accompanied by a 45-piece orchestra conducted by Gilles Bellemare, the 20-piece Vocalys Ensemble Choir, the English Rock Ensemble, and guest vocals by Jon Anderson, Annie Villeneuve, and Vincent Marois, with narration from Guy Nadon. The concert was accompanied by giant screens and a light and firework display. Wakeman has stated that this show was the highlight of his career.[citation needed]

Track listing

[edit]All music, narration, and lyrics written and produced by Rick Wakeman; all odd-numbered tracks narrated by Patrick Stewart.[2]

| No. | Title | Featured artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "A Vision" | 2:34 | |

| 2. | "The Return Overture" | 2:39 | |

| 3. | "Mother Earth"

| 3:48 | |

| 4. | "Buried Alive" | Ozzy Osbourne | 6:01 |

| 5. | "The Enigma" | 1:18 | |

| 6. | "Is Anybody There?" | Bonnie Tyler | 6:35 |

| 7. | "The Ravine" | 0:49 | |

| 8. | "The Dance of a Thousand Lights" | 5:41 | |

| 9. | "The Shepherd" | 2:01 | |

| 10. | "Mr. Slow" | Tony Mitchell | 3:47 |

| 11. | "Bridge of Time" | 1:12 | |

| 12. | "Never is a Long, Long Time" | Trevor Rabin | 5:19 |

| 13. | "Tales from the Lindenbrook Sea"

| 2:57 | |

| 14. | "The Kill" | 5:23 | |

| 15. | "Timeless History" | 1:10 | |

| 16. | "Still Waters Run Deep" | Justin Hayward | 5:21 |

| 17. | "Time Within Time"

| 2:39 | |

| 18. | "Ride of Your Life" | Katrina Leskanich | 6:01 |

| 19. | "Floating"

| 1:59 | |

| 20. | "Floodflames" | 2:00 | |

| 21. | "The Volcano"

| 2:10 | |

| 22. | "The End of the Return" | 5:23 | |

| Total length: | 76:51 | ||

Personnel

[edit]Credits are adapted from the album's CD liner notes.[2]

Musicians

- Rick Wakeman – Korg 01/W ProX, Roland JD-800, Kurzweil K2500R, Korg Trinity ProX, Korg X5DR, Technics WSA, Steinway concert grand piano, Minimoog synthesiser, Fatar SL 880, GEM PRO 2

- Justin Hayward – lead vocals on "Still Waters Run Deep"

- Katrina Leskanich – lead vocals on "Ride of Your Life"

- Tony Mitchell – lead vocals on "Mr. Slow"

- Ozzy Osbourne – lead vocals on "Buried Alive"

- Bonnie Tyler – lead vocals on "Is Anybody There?"

- Trevor Rabin – lead vocals, guitar on "Never is a Long, Long Time"

- Fraser Thorneycroft-Smith – guitar

- Phil Williams – bass

- Simon Hanson – drums

- London Symphony Orchestra

- David Snell – orchestra conductor

- English Chamber Choir – choir

- Guy Protheroe – choir conductor

Additional personnel

- Patrick Stewart – narration

Production

- Rick Wakeman – production

- Roger Dean – cover, booklet artwork, painting, drawings, lettering

- Martyn Dean – booklet design

- Simon Fowler – photography

- Frank Rodgers – executive producer

- Carolyne Rodgers – project co-ordination

- Candy Atcheson – project co-ordination

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1999) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Scottish Albums (OCC)[16] | 70 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[17] | 34 |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Rick Wakeman – Interview – Madrid, 21th [sic] April 1999". YesMuseum.org. 21 April 1999. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Return to the Centre of the Earth (Media notes). EMI Classics. 1999. 724355676320.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ward, Paul (July 1999). "Rick Wakeman: Recording Return to the Centre of the Earth". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ Pertout, Andrian (5 February 2003). "Rick Wakeman: Return to the Centre of the Earth – Part II". Mixdown Monthly, Beat Magazine. No. 106. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bollenberg, John (22 January 2000). "The Return of Rick Wakeman!". Progressiveworld.net. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ a b Popoff 2016, p. 141.

- ^ Return to the Centre of the Earth press release (1 October 1998).

- ^ a b Perry, Shawn (October 1999). "Rick Wakeman – Return to the Centre of the Earth". Vintage Rock (About.com). Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Single of the Week". Birmingham Evening Mail. 16 March 1999.

- ^ a b Convey, Kevin R. (13 June 1999). "Band hopes 'Astro' will also be a Smash; SMASHMOUTH Astro Lounge (Interscope) 3 1/2 stars". The Boston Herald. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Degagne, Mike. Return to the Centre of the Earth review Retrieved on 2009-10-03.

- ^ "Rock; BARENAKED Ambition". Coventry Evening Telegraph. 19 February 1999. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Smith, Aidan (5 March 1999). "The fall guy and the Yes man". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Popoff 2016, p. 140.

- ^ Batters, Paula (2 June 1999). "'Prog rocker' tours houses of the holy". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- Sources

- Popoff, Martin (2016). Time and a Word: The Yes Story. Soundcheck Books. ISBN 978-0-9932120-2-4.